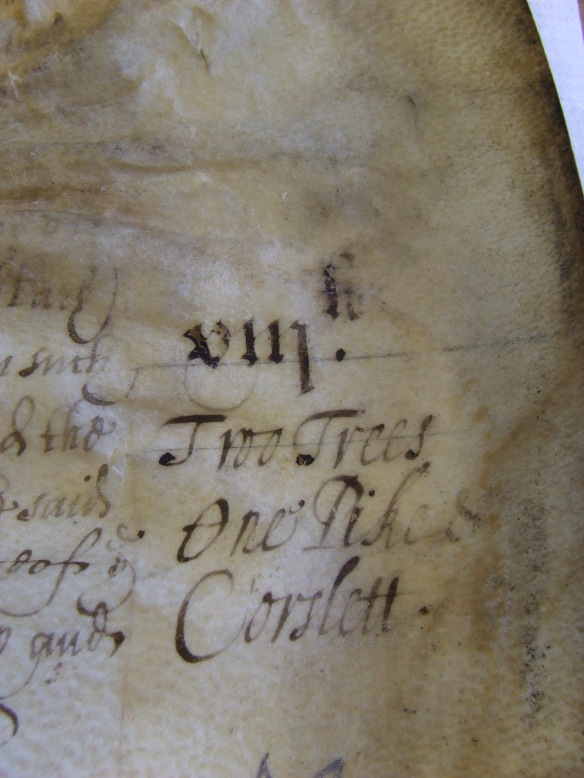

The Great Parchment Book website has gone live!

You can now start to explore the Great Parchment Book for yourself.

A good place to start is the video on the Home Page which illustrates the challenging nature of the project.

To continue your exploration, click on “Take a look inside the book” or search for a person, place or livery company.

If you want to know more about the historical background, book or project history, investigate the history tabs at the top of the Home Page.

The website is dynamic. Work is continuing on the transcription, and transcriptions and images will continue to be added to the site. Once the transcription is complete, the book history page will be expanded to take account of new insights into the codicology of the book, and to explain the arrangement of the folios.

The Great Parchment Book Blog is now embedded into the website and you can subscribe to the Blog on the website. Work is continuing to align the original Blog and the website Blog.

If you have any comments on the website, or can offer additional insights into the Great Parchment Book and what it reveals about the people, places and organisations involved in the history of 17th century Ulster, please share via the Blog or use the comment form at the bottom of the website Home Page.