We recently had our paper, Interactive Exploration and Flattening of Deformed Historical Documents, accepted for publication in the Computer Graphics Forum and to be presented at Eurographics 2013.

Our procedure begins by capturing a set of high resolution photographs of the pages of the book, and generating from them a detailed 3D scan of each page. Typically we need between 40 and 60 images per folio to capture every fold and crease in sufficient detail. Using these scans we attempt to “virtually restore” the pages and produce undistorted images of the pages.

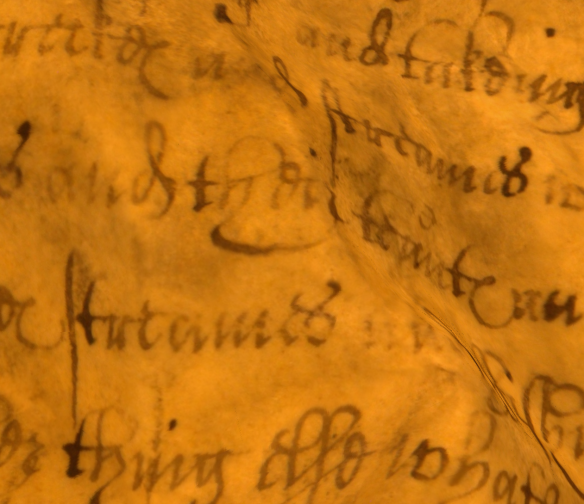

Three pages of the Great Parchment Book. Top: our reconstructed surface model. Bottom: the models textured with images of the text. The surface models show the level of distortion the parchment has suffered, which differs greatly from folio to folio.

Having generated scans for the majority of the pages in the book, we realized that producing a globally flattened and undistorted image of a page is not always possible for the more damaged pages due to the sheer variety and complexity of the deformations present.

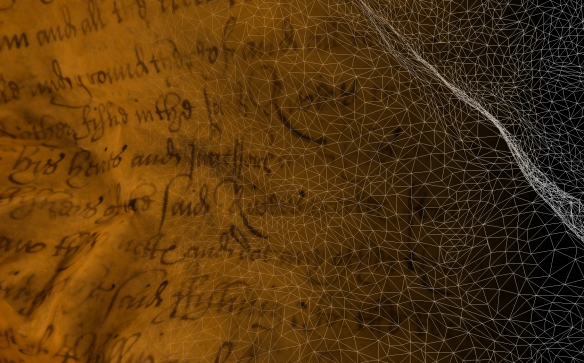

To get around this problem we instead created an interactive browser application, effectively a “Google Earth for documents”. Google Earth allows users to navigate over the surface of the earth following lines of latitude and longitude, and always see a locally flat map of the region of the earth they are looking at. In a similar way, our viewer allows users to navigate over the surface of the page following lines of text, and see a locally undistorted image of the region of the page currently in view. One of the key insights here is that flattening multiple small, local regions of a page is much simpler than flattening the entire page at once.

Regions of text before and after the local flattening procedure

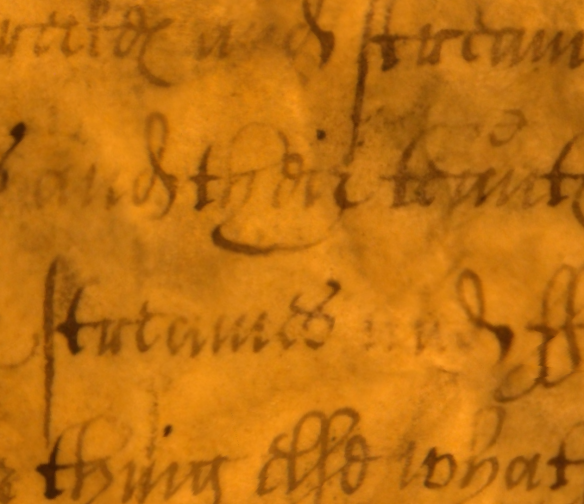

We also understand the importance in the digital cultural heritage field of being able to trust digital representations of artifacts. To help users gauge the quality of the reconstruction and be more confident in what they read, our application includes a “provenance feature” which allows them to compare the 3D scan and the original photographs which were used to generate the scan. For every point on the scan surface, the application can display an original input photograph next to it which allows the user to verify what they are seeing in the scan.

Left: A region of a reconstruction of a page, containing a suspect marking which looks like it might have been introduced by an error in the reconstruction process. Right: One of the original photographs, looking at the same region of the page. We can see that the marking is in fact present on the page.

Our application will soon be used as an additional tool for the transcription of the Great Parchment Book and possibly later as a means of dissemination of the book’s content.